He finished high school

He’s not ready for college

The battle over what to do next

Starting

College Behind

When 19-year-old Luis moved into a three-bedroom apartment in Chicago’s Belmont Cragin neighborhood with his mother, four siblings and baby niece last summer, his mom immediately set up the large family altar on a glass table in the dining room.

She draped rosaries over a Virgin Mary statue and placed family photos at the base. There’s a photo of Luis’ niece in a sunflower crown and funeral mass cards for relatives who have died, including a cousin who was shot by a gang member when Luis was nine. In the front sits a photo of Luis in a royal blue cap and gown from his eighth grade graduation.

In June, Luis wore a red cap and gown. This time, for his high school graduation. Another photo to add to the altar.

Growing up, Luis remembers his mom repeatedly telling him to finish what she hadn’t: high school.

Once he fulfilled her wish, the next step was up to him.

Photos of Luis and his family surround an altar in the home where he lives with his mother and five relatives. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

Photos of Luis and his family surround an altar in the home where he lives with his mother and five relatives. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

Late last summer, he decided to attend Wilbur Wright College, one of the seven two-year community colleges that make up the City Colleges of Chicago. He received financial aid to cover tuition and books. We’re not using Luis' last name at his request to retain some privacy online.

Luis hopes to eventually get a bachelor’s degree in industrial engineering and said he’s motivated by the idea of earning enough that he doesn’t have to worry about money. His mom works 12-hour days to support their large family.

But when he enrolled at Wright, he got some surprising news: He wasn’t ready for college.

“I just got out of high school doing four years and they’re telling me I’m not ready for this?” he remembered thinking.

Luis, in his signature grey hoodie, stands in front of Wilbur Wright College in January. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

Luis, in his signature grey hoodie, stands in front of Wilbur Wright College in January. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

Placing below college level

This fall, nearly two-thirds of new students at City Colleges were just like Luis. They placed below college level, either in math or English.

They were put in one or more classes known as developmental education. For decades, it was often referred to as remedial education. Students don’t get credit for these courses, and even though they cost money, they don’t count toward a degree.

These days, some kind of degree or credential after high school is vital in Illinois and across the country. Illinois has set a goal that 60% of residents have a postsecondary credential by 2025. Eight out of ten employers here say they need workers with a certificate or degree.

But few students who start in remedial education make it. Among all students who started at City Colleges in 2013 and needed remediation, just 11% graduated in three years.

It’s a national problem, too. Nearly 70% of community college students across the country took at least one remedial course, according to a 2016 report from the federal government. Just 26% earn an associate degree in three years.

The stakes are high. When students like Luis don’t succeed, many drop out and are left with few options for careers that allow for a comfortable life. If Chicago wants an economically thriving city for all, that can’t happen. The same could be said for the rest of the country.

“This is fundamentally an economic development issue, because if those students are coming back with degrees because they've been successful, then that brings dollars into our communities,” said Kyle Westbrook, executive director of Partnership for College Completion, a local group that works to improve graduation rates in northeastern Illinois.

But too few students are making it to graduation — and advocates like Westbrook think developmental education itself is the problem.

The push to end developmental classes

Westbrook is part of a movement across the country to overhaul developmental education — with many states and education advocates pushing to get rid of it all together.

Last year, the group brought that debate to Illinois when they tried to follow other states and spearheaded a bill that would have significantly scaled back developmental education. Instead, it would have required colleges to put most students directly in college classes with extra support. After that effort received pushback, they settled for a task force to examine how to improve developmental education programs statewide. Recommendations are due this summer.

Emily Goldman, policy manager with Partnership for College Completion, introduces herself during a November meeting of the state's developmental education task force at Governors State University. The task force was launched after a bill to significantly scale back developmental education was tabled. (Marc Monaghan for WBEZ)

Emily Goldman, policy manager with Partnership for College Completion, introduces herself during a November meeting of the state's developmental education task force at Governors State University. The task force was launched after a bill to significantly scale back developmental education was tabled. (Marc Monaghan for WBEZ)

The Partnership for College Completion and others believe students like Luis should go directly into college-level classes from the start, with extra support. It’s called the “corequisite” model, and it’s becoming popular nationally as states are adopting it en masse and seeing success.

But critics, including some faculty at City Colleges and across the state, say some students need more time and support. Without developmental classes, they argue community colleges, which are meant to serve everyone, wouldn’t be open to the most at-risk students. Often, students placed in developmental education are students of color, many of whom are the first in their family to attend college.

They fear these reforms will push out the students who struggle the most, those who drag down the graduation rates. Instead, those students will be funneled toward certificate programs where they could get an entry-level job faster, but wages aren’t as high.

And in Illinois, they aren’t giving up without a fight.

“We could do it better”

English faculty at Wright College remember when City Colleges wanted to fully adopt the corequisite model, starting at their campus.

“We all just kind of said ‘No, that we agree that we could do it better and give us the opportunity,’” said Tara Whitehair, a developmental English professor at Wright, where Luis enrolled in September. The teachers were suspicious of the overhaul and worried if students were placed in a class they weren’t ready for, it would force faculty to water down the college courses. They argued some of the reading and writing skills that students lack require practice and time, rather than just extra support as they go along.

“You can’t build the foundation for a house while you're putting up the walls,” Whitehair said. “For a lot of students, it’s a basic, strong foundation of literacy, and that takes time. You can’t do those things simultaneously.”

“For a lot of students, it’s a basic, strong foundation of literacy, and that takes time. You can’t do those things simultaneously.”

Faculty in Chicago and elsewhere believe those who want to get rid of developmental education ignore all the other students who might not be successful due to issues related to poverty, trauma or years of attending under-resourced K-12 schools. Developmental education was being used as a scapegoat, they said.

But to their surprise, City Colleges’ leaders allowed faculty to redesign the program to launch in fall 2015 at Wright. They called it ARC: Aligned Reading and Composition.

They reduced the number of developmental English classes a student might need from four to one, and combined reading and writing instruction into one class. Previously, they were taught separately. They also improved the curriculum and created their own more holistic placement test.

“Part of our curriculum, too, for ARC is that confidence building and building that sense of community and that sense of belonging,” Whitehair said.

This is the English class that Luis enrolled in back in September.

Luis meets with Professor Susan Grace to discuss his performance in her developmental English class. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

Luis meets with Professor Susan Grace to discuss his performance in her developmental English class. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

Despite months of requests, City Colleges would not allow WBEZ in Luis’ classroom for this story, citing student privacy concerns.

Luis is a quiet student with a shy laugh. He’s never without his headphones and grey sweatshirt. He can spend hours trying to beat the next level of his video games or playing pickup basketball games with his brother. When he was in high school, the basketball team motivated him to maintain his grades, even though he never really felt connected to school.

Once he placed into developmental classes, he said he felt apprehensive about college and questioned if he should wait a year. But he knows himself: If he didn’t immediately enroll, he’d likely never return. Still, he said he felt stupid knowing he wasn’t considered ready for college.

Whitehair and other faculty push back against the idea that their students are stupid or illiterate. Many simply haven’t learned some important skills necessary for college and life, like reading comprehension, organizing ideas and critical thinking.

“When I ask them to go to a [reading] and say, ‘What is this text saying? Put this into your own words’ … they can't,” said Carrie Mocarski, a Wright College English professor who also had a long career as a high school teacher. “They can't comprehend the writing. ... Generally we're not talking about academic journals, we're talking about newspaper articles.”

Students also haven't learned to write academic essays. Many don’t know how to craft a thesis statement or cite research. They struggle with sentence structure, topic sentences, vocabulary and grammar.

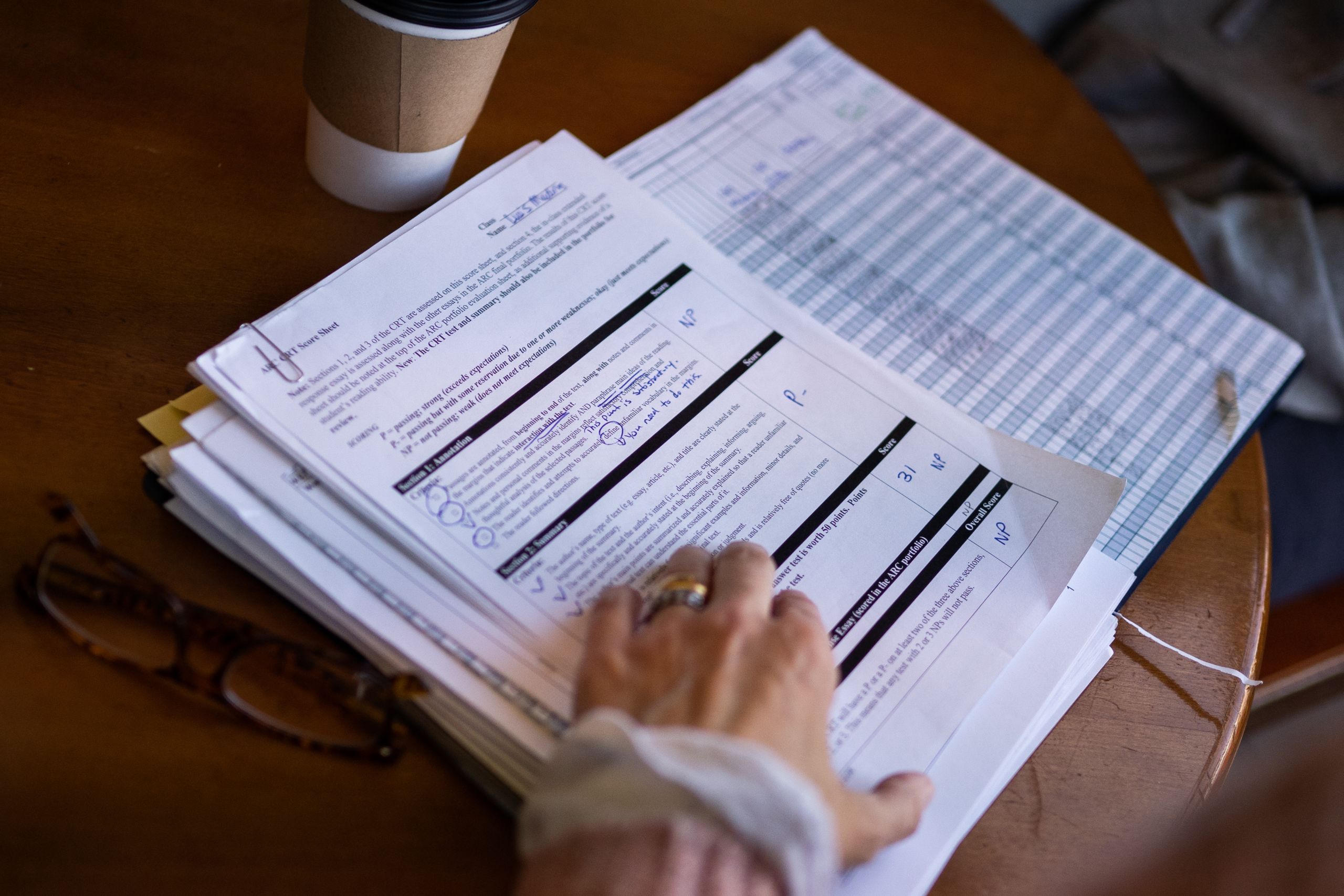

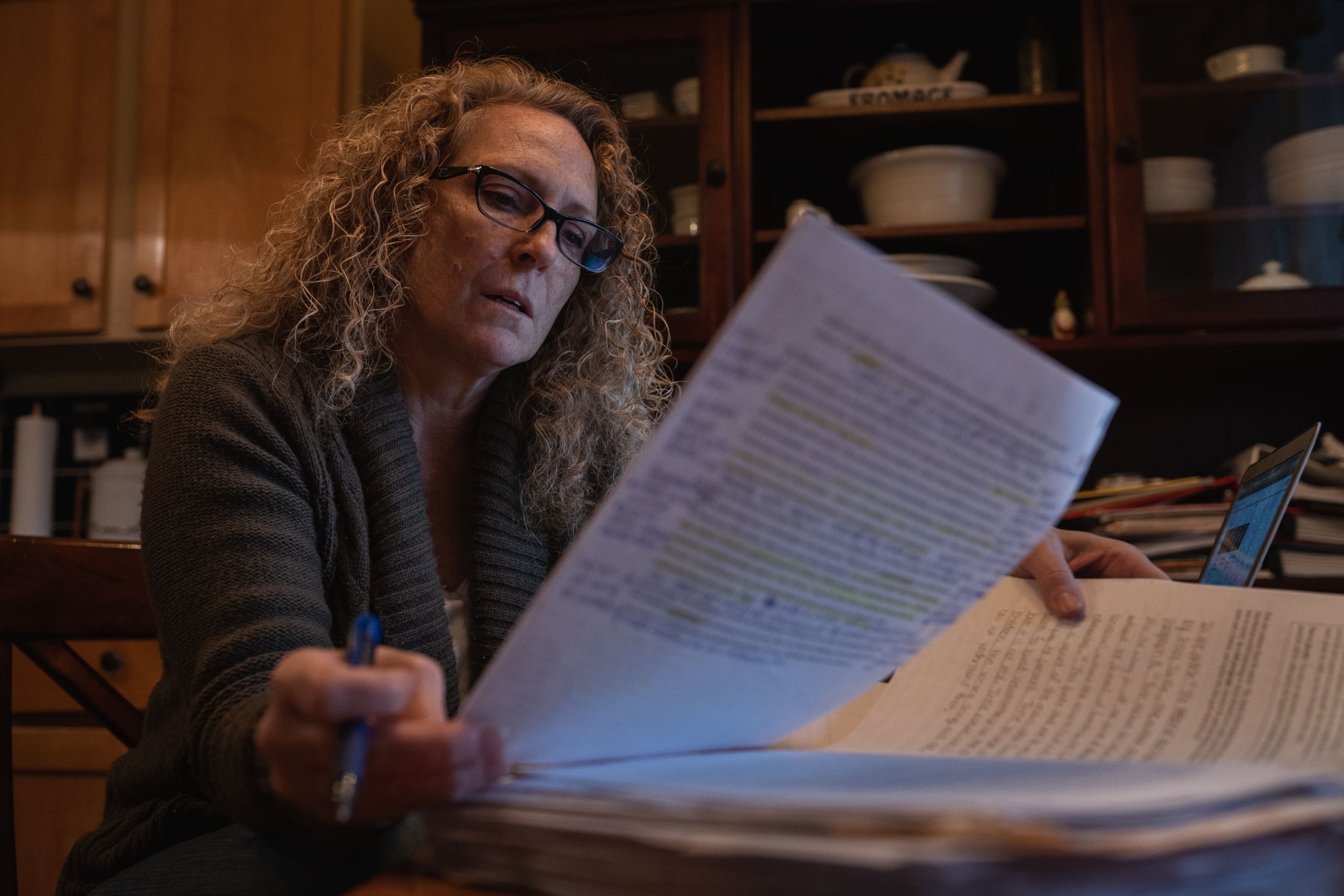

Wilbur Wright Professor Carrie Mocarski reads her students' essays in her home. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

Wilbur Wright Professor Carrie Mocarski reads her students' essays in her home. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

That’s where Luis was in September and October, in the first half of his fall semester. The first draft of a key essay was disorganized and contained more summary than analysis. He didn’t think he was a good writer and dreaded writing assignments, which led him to put them off until the last minute.

“I don’t know if it’s good or it’s organized right or have the right structure or [if] I’m … rambling my words,” Luis said.

But as the semester progressed, he started to become more engaged. He enjoyed the book assigned in class, James Baldwin’s If Beale Street Could Talk, and began to speak up during small group discussions. He said it’s the first book he read cover to cover since middle school.

The national conversation

How best to help students like Luis isn’t a new issue. Remedial classes have been around for decades and there have been waves of debate about whether they work.

The latest began when President Barack Obama was turning his focus to the United States’ lagging college graduation rates. In a 2010 speech, then-Education Secretary Arne Duncan laid some blame on K-12 schools.

“The truth is states with low standards have been lying to children and families for years, telling them they're ready for college and work when in fact they’re not even close. Many of those who attend college today need remedial education, and half of them drop out,” Duncan told the crowd. “The U.S. ranks 10th in the world in the rate of college completion for 25-to 34-year-olds. We were first a generation ago, and we want to be first again.”

Then-U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan speaks during the closing session of the White House Summit on Community Colleges in 2010.

Then-U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan speaks during the closing session of the White House Summit on Community Colleges in 2010.

This new national conversation quickly turned to why so many students weren’t making it out of developmental courses. Researchers, with access to better data, homed in on remedial education and found plenty of room for improvement.

One problem: Many students were required to take multiple remedial classes before actually going into college classes. There were too many opportunities to drop out. Researchers also discovered many students were wrongly placed in remedial education by inaccurate placement tests when they possibly could have succeeded in college-level classes.

Taken all together, developmental education was labeled “a bridge to nowhere.”

Education advocates, with deep pockets supported by groups like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Lumina Foundation, said too many students were wasting time and money in these courses. Instead, they said students should go directly into college-level courses and receive extra support.

This model started taking off around the country, and reformers in Illinois took notice.

“It’s kind of like fighting the ocean”

Over the past few years, City Colleges ramped up the new faculty-created developmental English program across the seven colleges, while also introducing more corequisite classes. At the same time, many states were taking more dramatic steps.

Florida allowed students to choose if they wanted to take remedial classes. California is shifting to all corequisite courses. Tennessee mandated all community colleges place students traditionally needing remedial classes into corequisites. Studies show the states making the change are seeing more students pass their introductory college-level course in the first year than before.

Last year, Illinois lawmakers filed a bill that would place all students like Luis directly in college courses with extra support. The legislation was scaled back and ultimately tabled for the task force, with recommendations due this summer. In an interview in December, Westbrook, whose group wrote the bill, refused to discuss the legislation, repeatedly saying it is focused on the task force.

But the story from Texas may have lessons for Illinois. In 2017, Texas passed a nearly identical law to the one proposed in Illinois. All community colleges in Texas are required to place 75% of students in corequisite classes by next fall. If this push is successful, Texas education leaders say they plan to place 100% of students.

Gene Voss has taught at Houston Community College for over three decades. He said he was initially skeptical of the changes.

“You're forcing people into a course, you know, that they’re not prepared for,” Voss remembered thinking. “But that hasn’t been the situation for the vast majority for me.”

Most of his students have successfully completed English 101 with the support class. Houston Community College leaders say they have put everyone in corequisites, regardless of skill.

Still, Voss and his colleague Victoria Trotter-Washington said they’re concerned about what happens to lower-skilled students.

“How do you tell a student [that if] you are not able to write an essay that you just don't belong in college?” Trotter-Washington said. “You don't have an opportunity or chance to work, to bring your skills up and to work better to improve yourself.”

“How do you tell a student [that if] you are not able to write an essay that you just don't belong in college?”

By creating the task force, Illinois is being more intentional than other states that mandated top-down reforms.

So far, there’s been plenty of discussion about following the national movement to place students directly in college courses with supports. There’s also interest in a new state initiative where high schoolers who are considered underprepared for college can take a course to build their skills during senior year. The state has rolled out those courses for math and is developing them for English.

However, many task force members support the mission of developmental education and bristle when it’s called a barrier for students. The bill’s sponsor, Illinois state Sen. Pat McGuire,D-Joliet, said it’s been a learning experience for him. He concedes the issues can’t be solved by just mandating one program. That’s welcome news for faculty members who disliked the bill.

But Voss at Houston Community College said it’s difficult to push back against these kinds of movements.

“It’s kind of like fighting the ocean,” he said. “It’s just going to keep coming.”

Illinois State Sen. Pat McGuire, listens to the discussion during a November meeting of the state task force examining developmental education. The task force's work began after McGuire sponsored a bill that would have reduced developmental education in Illinois schools. (Marc Monaghan for WBEZ)

Illinois State Sen. Pat McGuire, listens to the discussion during a November meeting of the state task force examining developmental education. The task force's work began after McGuire sponsored a bill that would have reduced developmental education in Illinois schools. (Marc Monaghan for WBEZ)

That’s one reason faculty in Illinois are concerned the task force is just delaying the inevitable: eliminating developmental education.

“I now have to fight a battle with people who are absolutely ignorant of the issues and are so far removed from my student population, these people that I love, that I come into work every day because I know them, because I've been them,” said Keith Sprewer, who has been teaching developmental English at Harry S Truman College in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood for a decade.

Sprewer is tall with a bright smile and a magnetic energy that draws in everyone at Truman, from the custodians to former students he runs into across campus.

Keith Sprewer talks to a student in one of his developmental education courses after class outside of Harry S Truman College in Chicago's Uptown neighborhood. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

Keith Sprewer talks to a student in one of his developmental education courses after class outside of Harry S Truman College in Chicago's Uptown neighborhood. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

He grew up in Milwaukee before moving to Chicago for graduate school. He said his high school didn’t entirely prepare him for college either, and he struggled particularly in college English. He credits constant visits to the library and Bible study with helping him develop the important critical thinking and reading comprehension skills his students lack.

Sprewer isn’t against putting more students in English 101 with the support class, especially students on the cusp of being college ready. Much of the research focuses on these students and shows corequisites work extremely well for them.

“[But] what about the person who has been out of school for a little while and has regressed? Or maybe never had it to start with, and now they figured it out,” Sprewer said. “If this space for them to kind of on-ramp themselves into what an academic life looks like didn't exist, [then] it’s another denial of access.”

Getting to graduation

Even if the state task force doesn’t eliminate developmental education, faculty are concerned City Colleges might make changes to their own programs. This fall, City Colleges leaders created their own task force to study how to improve developmental programs in English and math, which has remained untouched over the years. A plan is due April 1.

English faculty feel City Colleges leaders aren’t giving the program they designed a chance and say it will take time to see its impact. It’s true, there’ve been so many changes over the past few years that it’s difficult to say what’s working well. They have data showing modest improvements in pass rates in developmental English, as does City College leadership regarding pass rates for students in English 101 with the support class.

What we do know for sure is that City Colleges students who aren’t in remediation return to school the following year at higher rates than those who start in remediation, according to the Illinois Community College Board. They also graduate at higher rates.

Teachers said that’s not surprising since students in remedial education come in with weaker skills and could be more easily deterred. Plus, the new developmental English program was only scaled up across the seven colleges two years ago, so they say it’s too early to see its true impact.

Still, City Colleges administrators think more students could succeed in the corequisite class and have moved more students into it over time. Westbrook, with Partnership for College Completion, would agree with leaders at City Colleges: If putting more students in college courses with extra support shows promise across the country, then why wait?

“Does something have to be 100% before the state or an agency or institution actually moves forward with it, or can we see this is our best bet for getting more students to graduate?” Westbrook said.

But a recent study out of Tennessee found that even though the large-scale transition to corequisites has led to more students passing that first college-level course, it didn’t improve graduation rates at all. Researchers said reforms that have improved graduation rates are multifaceted.

“Colleges need to support them with enhanced advising, academic and career services, financial aid, and more structured pathways to degrees,” the report said.

“You’re on the cusp”

By the middle of the fall semester, Luis was still struggling. He had missed a few classes to take care of his sick grandmother and because he was sick, and he was often doing the bare minimum to pass.

There were some signs of increasing confidence and growth — and a recognition he had a lot to learn. “Some of the things she’s teaching us, I’m like ‘Damn, I didn’t even know about this,’” Luis said, laughing sheepishly.

But he had missed some classes where they’d gone over important assignments.

Luis didn’t pass the midterm, which was a practice for the final exam coming up in six weeks. He also just got a job at Portillo’s restaurant, working 40 hours a week, another responsibility.

Luis drives home from class at Wright College one day this fall. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

Luis drives home from class at Wright College one day this fall. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

When he met with his professor, Susan Grace, she told him she wanted to see him make an argument of his own in an essay, to show he’s thinking through ideas rather than just writing what he thinks she wants to hear. That is the kind of confidence building this developmental course is designed to encourage.

“You’re on the cusp. You need to be pulling it together,” Grace told him.

Luis' professor professor Susan Grace told him mid-semester that he had to show he could think for himself in his writing. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

Luis' professor professor Susan Grace told him mid-semester that he had to show he could think for himself in his writing. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

If he failed, he’d need to retake the developmental class.

Meanwhile, Sprewer was having his own frustrations with students. When he gave the midterm, half of the students didn’t bring the reading they needed, even though he reminded them via text message earlier that morning. He said those who did bring the reading hadn’t read it.

For Sprewer, this is the type of behavior that the reform movement ignores. Is this caused by the fact that a student is in developmental education, he asks, or, does it have to do with the student?

“And I’m not even suggesting that this is a lazy student,” he said. “[It could be] a student with children, a student that has to work, a student that is homeless. There are all sorts of reasons students are not successful that have nothing to do with curriculum.”

Does everyone need college?

As Luis continued through his semester, he still wasn’t convinced it was worth the effort. He was tempted to drop out and work.

“I mean, [my mom] did just want us to graduate high school,” Luis said. “She's not going to like push me to go into college. I did that on my own.”

Luis said he wanted college for himself and that is the messaging students often receive in high school. They need a plan to graduate from a Chicago public school and often that includes college.

But does everyone really need college? Maybe Luis would be better off pursuing a certificate or a trade?

Keith Sprewer says that message is sent to certain students more than others.

“We're telling black and brown children and poor children that you should go into the trades,” Sprewer said. “The reality is we haven’t prepared them. So when we talk about the trades, we like to think electrician, plumber … those are licensed trades. The students that we were talking about that show up in my class couldn't take the test to get the licenses to go into those trades that make so much money.”

Instead, he said, “they'll be going more to these other trades that are rapidly being automated … like supply chain management, or the service industry, transportation.”

English Professor Keith Sprewer at his office at Harry S Truman College, where he has taught developmental English for 10 years. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

English Professor Keith Sprewer at his office at Harry S Truman College, where he has taught developmental English for 10 years. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

Last year, WBEZ found students pursuing certificates and degrees in heating, ventilation and cooling at City Colleges struggled with basic math skills needed to earn those degrees. A WBEZ series on Chicago’s manufacturing sector also reported many students who enter privately run training programs need remedial education.

Besides, Luis said he doesn’t want to pursue a certificate; he wants that degree. Faculty said that’s the whole point of developmental education: giving students a place to build the skills they need so they can make the choices they want. It’s not up to them or anyone else to decide a student’s path.

Over the last few weeks of the semester, Luis’ teacher, Susan Grace, said she saw a lightbulb go off in his head.

All the things he had been learning were beginning to gel. When they were discussing his final paper, he admitted he disagreed with Grace’s opinion in class.

She told him that’s just what she wants.

Ahead of his final writing assignments, Luis' professor Susan Grace said she began to see things gel for Luis. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

Ahead of his final writing assignments, Luis' professor Susan Grace said she began to see things gel for Luis. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

The final test

In early December, Grace met two other professors at a crowded coffee shop in Rogers Park.

Students in developmental English at City Colleges must complete a successful writing portfolio to advance to English 101. Three teachers review each portfolio, including Luis’. He gave me permission to attend his review session.

The two professors read his papers quietly as Grace waited.

“What are you thinking of this?” Grace asked expectantly.

The verdict: “The difference between this first draft and third draft is remarkable,” one of the professors said enthusiastically.

“I know!” Grace exclaimed. “It’s night and day. He finally worked.”

Luis laid out his own argument and was able to back it up. His sentence structure and grammar also improved.

The three professors weighed in with a final decision: He passed. He can go on to English 101.

“I know more than what I did in the beginning”

It’s impossible to say whether Luis would’ve done well if he was directly placed in English 101 with the support class. Would he have been more motivated knowing he was getting college credit? Or would he have felt in over his head and decided this whole college thing wasn’t for him?

Luis said he doesn’t know either. But it’s clear he learned a lot this fall.

“Honestly, this semester of college taught me more about going into college than high school did in the four years I was in there,” he said.

He felt like high school was kind of a waste and accepts some responsibility. But he says what he learned in high school was so different than what he actually needed to be successful in college.

“At the beginning of the course, I was biased in why I was in this class,” Luis wrote in a final essay for his developmental English class. “I thought I knew everything and didn't need the class. But coming out of this class, I know I know more than what I did in the beginning. I see this because I catch myself using multiple vocabulary words we learn in my day-to-day life. I feel more prepared and confident than the beginning of the course to go into 101.”

He said he’s sad to leave the class because everyone developed a bond with the teacher.

“Honestly, this semester of college taught me more about going into college than high school did in the four years I was in there.”

On the last day of the fall semester, Luis ran into his advisor. At first, she didn’t recognize him; her caseload is so huge. There are 429 students to every one counselor at City Colleges — the national average for community colleges. When Luis reminded her that he’s pursuing engineering, she took him to Wright’s engineering center to introduce him.

Luis sat down with a staff member who peppered him with questions about his interests and why he chose engineering, but Luis couldn’t answer most of them. The more she asked, the more he seemed to shrink in his chair.

When Luis left, he seemed overwhelmed.

“That’s so much information I just got today,” he said wearily as he walked to his car.

Luis’ inability or decision not to engage, even after he knows he’s passed his developmental class, is a reminder he still needs so much help figuring out how to build confidence, to motivate himself, to push through the next two years. Some of that needs to come from school, his advisors and teachers, and some of it from within himself.

Luis near his home on Chicago's Northwest Side. If things go well at Wright College, Luis says he wants to go on for a bachelor's degree in engineering. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

Luis near his home on Chicago's Northwest Side. If things go well at Wright College, Luis says he wants to go on for a bachelor's degree in engineering. (Pat Nabong for WBEZ)

If Luis succeeds, it won’t just be a victory for himself. It’s what all the task forces are studying and trying to achieve. It also will move the city one person closer to what local politicians and advocates say Chicago needs: an economy that works for everyone.

Luis started English 101 in January. He says the class is “way different” than last semester. The class jumps right into discussions with fewer instructions. Still, he said he feels more prepared and more confident in his writing.

Some of his old habits are reemerging. He hasn’t really opened the book for class yet, and he isn’t talking much. But he knows he needs to be here if he wants that degree, that higher salary, that life he hopes for.

For now, he’s still showing up.

Kate McGee reports on higher education for WBEZ. You can follow her on Twitter at @McGeeReports.

This story was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.

Credits

Editor: Kate Grossman

Photographs: Pat Nabong and Marc Monaghan

Design: Paula Friedrich

How we reported this story

When every radio journalist starts a reporting project, they have a grand vision for what a perfect story sounds like: the emotional sound bites, the perfect scenes.

In many cases, that doesn’t happen. This story was no different.

When I embarked on this project, with the help of a grant from the Education Writers Association, my plan was to do a deep dive into a faculty-created program at City Colleges of Chicago for students who are deemed underprepared for college English. It’s called ARC: Aligned Reading and Composition.

I found four teachers at Wilbur Wright College who were willing to let me embed in their classrooms for a semester to see how the program worked and whether it was helping students succeed.

I approached City Colleges’ district office with my request on June 17, 2019. Throughout the summer, City Colleges media relations repeatedly said they were considering the request. Finally, on Sept. 6, after the start of fall semester, I received notice that the request was denied. City Colleges and Wright College leadership had concerns about disrupting student learning and their privacy, despite support from faculty. We tried to assure City Colleges that we would be cognizant of students who did not want to be recorded and amenable to their request for privacy. We explained that as a public institution paid for with taxpayer dollars, it’s vital that our listeners and readers understand what’s happening in the classroom. However, leadership was not swayed. The mayor’s office supported City Colleges’ decision.

Then, we found a teacher at Harry S Truman College, where the president was receptive to the idea but said City Colleges leadership would make the final decision. They offered us access to one class period after securing student permissions.

We made multiple requests for permission to visit the classroom to explain the project and answer student questions. Those requests were denied. When a school leader ultimately spoke to the class about the project, at least one student had concerns and we were not allowed in that class. When WBEZ asked City Colleges to find another class for us to visit, that request was never fulfilled.

Ultimately, the last week of class, City Colleges allowed WBEZ to wait outside a computer lab at Wright College to talk to students as they registered for the spring semester. City Colleges also found one student at Truman College for WBEZ to interview.

As all this was unfolding, I started to contact students through other routes and met Luis, the student I profiled and who graciously allowed me to follow him throughout his fall semester. We chose to follow Luis because, in many ways, he is a typical student placed in developmental education.

Since I wasn’t able to observe or record Luis in the classroom, I followed him in other aspects of his life: playing basketball or video games. I had him read his essays and classwork out loud. I also found teachers willing to speak with me throughout the semester about their experiences teaching the class. I spent time with them at their homes or on their commutes. Throughout the semester, we also interviewed former developmental English students who did not make it into this piece, but their stories informed our reporting. I also interviewed national and local experts, read hundreds of pages of research and attended a national developmental education conference.

I also tried to get student-level data (with identifying information redacted) from City Colleges through Freedom of Information Act requests. I wanted to capture the progression of students through developmental education courses and beyond to see how they make their way from high school to the college graduation stage. Multiple requests were partially or fully denied by City Colleges’ general counsel’s office, which argued the information we requested was “a new record” that they say they do not have to legally provide. Instead, City Colleges provided WBEZ with PowerPoint decks of their own data analysis. A request for the raw data behind those slides was ignored.

The inability to visit City Colleges’ developmental English classrooms forced us to broaden the focus of the story, which ended up being a positive pivot. There’s a fascinating, contentious debate currently happening in Illinois and across the country about the best way to help underprepared students succeed in college.

That debate took us to Texas. Three years ago, Texas passed a law nearly identical to one proposed — and ultimately tabled — in Illinois. So, we went to Austin and Houston to see how it’s working so far. In contrast to City Colleges’ approach to media, the colleges in Texas welcomed us into the classroom. We visited developmental English programs at Austin Community College and Houston Community College where we were able to interview students, talk to teachers and see how these schools were using a new model that puts students directly in college-level classes with extra supports.

It’s unclear how this debate over developmental education programs will play out in Illinois, and I’m excited to continue covering this issue. Truman College English Professor Keith Sprewer argues it’s one Chicagoans should continue paying attention to, even if they have no connection to City Colleges.

“We're only as good as the person who is most vulnerable,” Sprewer said at the end of the fall semester. “We should have some stake … in the well-being of every member of our community.”

Stay tuned. We will be.