-

What would the city

look like today?

A thought experiment conducted by WBEZ’s Curious City, inspired by a question posed by Chicagoan Kevin Borgia.

Story by Robert Loerzel

Produced by Logan Jaffe | Illustrations by Erik N. Rodriguez

I. Our thought experiment

What if one of the most famous events in Chicago history — the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 — never happened? What would the city look like today?

Kevin Borgia asked WBEZ’s Curious City to find out, giving us an assignment that’s a bit like imagining an alternate universe. Of course, there’s no way of really knowing how history would have changed if that fire hadn’t swept across more than 3 square miles of Chicago on Oct. 8, 1871, destroying 18,000 buildings, killing some 300 people and leaving 100,000 homeless.

What we can offer are educated guesses from historians, authors and experts on Chicago architecture. We posed Kevin’s question to more than a dozen knowledgeable sources. We pored over books on the city’s history.

And what did we find? Not just one alternate history, but a whole array of parallel universes — different versions of Chicago. As Northwestern University professor Carl Smith told us, “Once you open up what might have happened, the possibilities are endless.”

But this was more than a mere exercise in fantasy. Kevin’s provocative question sparked a fascinating debate on how one event can shape a metropolis.

Kevin, who is 34, grew up in Chatham, a small town near Springfield, but he has lived for the past decade in Chicago, where he works for the group Wind on the Wires, advocating for wind power. “I’m fascinated with the history of the city,” he says. After reading books on the city’s history and hearing people talk about the Great Chicago Fire, he started to think about how much it seemed to shape “the way that our city is.”

“Once you open up what might have happened, the possibilities are endless.”

-Carl Smith

“To a huge degree, the design and layout of the city of Chicago and the character of the buildings are a result of the Chicago Fire,” he says.

“If the fire hadn’t happened, it would look a lot different.”

To answer Kevin’s question, let’s first consider the possibility that a different fire would have destroyed a large section of the city sooner or later. Chicago was filled with wooden buildings, as well as piles of lumber and coal. And the city had 561 miles of wood sidewalks. It seemed destined for destruction.

Richard Bales, author of The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow, pinpoints a date when an alternate-history disaster might have struck: July 14, 1874. That’s when a fire began near Taylor and Clark streets in the South Loop, sweeping across 60 acres but stopping short of the central business district.

“The fire stopped burning when it hit the newly built stone buildings in the business area,” Bales says. “Assume that there is no Chicago Fire of 1871. Then it is possible that the 1874 fire ... would have burnt even more properties.”

But let’s say Chicago somehow managed to avoid a devastating fire. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 didn’t happen. Neither did that fire in 1874 — or anything on a similar scale. Then what?

“Chicago would probably have been a much smaller metropolis and not the second-largest city in the United States,” says Neal Samors, author of several books on the city’s history. He argues that the fire’s clearing effect allowed a building boom that wouldn’t have been possible without the fire.

But several historians told us that most of the changes that occurred in Chicago after the 1871 fire would have happened anyway — only at a slower pace and with subtle differences.

“Chicago’s perfect central location for commerce would have remained constant — the city would have continued to grow,” says Tim Samuelson, the city of Chicago’s cultural historian.

And Tom Leslie, author of Chicago Skyscrapers: 1871-1934, wonders if Chicago would be much different at all. “I have to say that the city today doesn’t really owe that much to the fire itself,” he says.

II. Buildings &

neighborhoods

A photograph taken from the top of Chicago's old City Hall, looking Southwest. (Alexander Hesler, 1858)

Here’s the most obvious thing that would be different in a world without the Great Chicago Fire — those 18,000 buildings wouldn’t have burned down in the fire zone (which stretched from the O’Leary family barn — on De Koven Street in what is now the South Loop — across downtown and up to Lincoln Park). But how many of those buildings would still be standing today if the Great Fire hadn’t happened, and would that have changed city neighborhoods?

David Garrard Lowe, author of Lost Chicago, says several major buildings might have survived. One is architect John Van Osdel’s Cook County Court House and City Hall, a domed structure with a cupola, built in 1853 where City Hall stands now. The courthouse’s bells rang out during the 1871 fire, a baleful alarm in the midst of the inferno.

A beautiful hotel by the same architect, the Tremont House at the southeast corner of Lake and Dearborn streets, might have survived too, Lowe says — along with gems like the Grand Pacific Hotel, Crosby’s Opera House, the Academy of Design and the original Chicago Historical Society. And Lowe says the churches that once dotted downtown could still be standing, along with some of downtown’s mansions.

"Indeed, in some ways, we might have had a more humane metropolis."

-David Garrard Lowe

“The old houses on Monroe and Wabash were handsome and would have given downtown Chicago a certain elegance and variety,” Lowe says. “Of particular importance were the houses on Michigan Avenue, including the one where President-elect Lincoln and Mrs. Lincoln were guests before they entrained for Washington. Think of what distinction the 19th-century houses on Beacon Hill give to downtown Boston, as well as the enrichment New York receives from the Greek Revival row houses on Washington Square.”

Lowe says Chicago’s central business district might have been forced to expand toward the west if the fire hadn’t cleared so much land. Imagine a skyline with more skyscrapers west of the Loop.

“The Loop would not have become a series of skyscraper canyons,” Lowe says. “There may have been more green spaces in downtown Chicago. … The square in which the courthouse sat had trees, and the old houses had gardens and lawns with shrubbery and trees. Indeed, in some ways, we might have had a more humane metropolis. … How nice it would have been to have green oases in the heart of the Loop.”

But Samuelson says a tall, dense downtown was inevitable. “Downtown would have still been hemmed in by immovable natural, physical and commercial barriers, so the need to build tall buildings very likely would have become a necessity as the city continued to grow,” he says.

Leslie suspects downtown residences would have been swept away by the building booms of the 1880s and 1890s. “South Michigan Avenue … was residential from about where the Auditorium is now until the turn of the century,” he says. “Many of the mansions along the southern stretch disappeared without a trace when the land became valuable as commercial opportunities. It’s possible that one or two really grand structures might have survived the onslaught, but certainly not many.”

Another neighborhood that might be a lot different, Leslie says, is River North. Many of the buildings that burned down in River North might still be standing, he says.

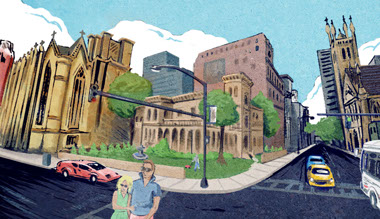

Compare:

A humane metropolis

For our what-if scenario, David Garrard Lowe, author of Lost Chicago, considers the effect of so many homes and landscaped areas being spared in downtown Chicago, had the Great Fire not happened. “Indeed, in some ways, we might have had a more humane metropolis,” he says. (Image: Google Earth / Illustration: Erik Rodriquez)

“Development there really only occurred after the 1960s, when preservation legislation came into effect,” Leslie says. “Most of that neighborhood was residential or industrial, and it’s possible that those (buildings) would have been reused — or at least not torn down — through then. You can imagine that the whole neighborhood might have become a historic district.”

If Leslie’s correct, the Magnificent Mile and all of those shops, restaurants, offices and condo high-rises north of the river might not exist in our bizarro-world version of Chicago.

Without the Great Fire, we’d probably see more Greek Revival buildings in Chicago, says Jennifer Masengarb of the Chicago Architecture Foundation. The fire destroyed many structures in this style, which was common in churches, banks, public buildings and large homes built from 1830 to 1850.

“By the time we began rebuilding in the 1870s, Greek Revival had fallen out of fashion, and so the next wave of construction looked quite different,” Masengarb says. “One great surviving example of this style is the Clarke House, 1827 S. Indiana Ave., built in 1836.”

Masengarb also believes that some of Chicago’s wood-framed two- to three-story cottages, which had simple gable roofs and horizontal siding, would survive today.

“They can be seen in neighborhoods like Old Town, along Menomonee Avenue, between Sedgwick and Wells,” she says. “Old Town is an interesting case study because while the whole area burned in the fire, it was rebuilt right after the fire — largely in the same manner as before. … Old Town provides a glimpse of what pre-fire Chicago looked like.”

Wood-framed, two-to three-story cottages such as these in Chicago's Old Town neighborhood provide a glimpse of what the city looked like before the fire. (Image: Google Earth).

And without the fire, Chicago would have more brick single-family Italianate-style homes, Masengarb says. “Before the fire, we had more of these two-story homes with a low-pitched roof, wide overhanging eaves and decorative brackets,” she says. “South Michigan Avenue was a residential quarter lined with Italianate homes — called ‘Park Row,’ it ran along Michigan Avenue near 12th Street.

“We can certainly see pockets of Italianate through the city today — a few rebuilt in Lincoln Park after the fire,” she says. “We also see pre-fire row house versions of Italianate along Archer Avenue — far outside the burn district — and some post-fire versions along Jackson Boulevard just east of Ashland. But for the most part, we did not rebuild these single-family Italianate versions in Chicago. You see them all throughout towns in Illinois as well as the older suburbs.”

But some experts say few buildings destroyed by the 1871 fire would still be standing today. “Most were made of wood,” says Joseph Schwieterman of DePaul University. Samors says, “Fires would have been inevitable.”

And many would’ve been torn down. “Most likely they would have been demolished for larger and newer buildings as time passed — certainly by the 1920s and the 1950s,” architecture critic Lee Bey says.

Terrace Row, fashionable residences along Michigan Ave., is an example of Italianate architecture that may have been more prominent throughout the city if the fire hadn't happened. Terrace Row was destroyed in the fire. (Photo courtesy New York Public Library)

Terrace Row, fashionable residences along Michigan Ave., is an example of Italianate architecture that may have been more prominent throughout the city if the fire hadn't happened. Terrace Row was destroyed in the fire. (Photo courtesy New York Public Library)

As any aficionado of Chicago architecture knows, the city doesn’t have the most stellar track record for preserving old buildings, even treasures created by brilliant artists like Louis Sullivan. “As you know,” Smith says, “a lot of magnificent post-fire buildings have been torn down.”

“It seems unlikely more than a few fragments would have survived,” Leslie says. “All of the buildings that burned were five stories or less, and none of them had the large open floor plates that have been crucial for converting older office buildings to newer ones. A handful of civic buildings — the old courthouse, for instance — might have been kept for historic value, but even that might well have been torn down and replaced.”

Ann Durkin Keating, co-editor of The Encyclopedia of Chicago, agrees that few pre-1871 structures would still be standing. “But there would be more buildings with iron fronts, five to six stories, around downtown,” she says. “We have very little of that world left, but can see it in Galena, Springfield and other places that did not grow like Chicago.”

Schwieterman says many of the buildings destroyed by the 1871 fire would have lasted for a while — possibly until the early 1900s. Then they would’ve been torn down to make way for buildings in 20th-century styles. “We would not have the rich collection of building dating back to the 1875-1903 period that we have today,” he says. “Instead, we would have a larger stock of buildings of more recent vintage.”

III. Changes: Building materials

During the rapid reconstruction after the fire, builders had trouble finding enough stone to put on their facades and terra cotta become a more common building material. Above: An ornamental terra cotta false front on a commercial building on W. Chicago Ave. (Terence Faircloth/Flickr)

The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 also affected the choice of materials used in the city’s buildings. It was a major factor in the City Council’s decision to restrict the construction of wooden buildings.

Three months after the 1871 fire, Chicago Tribune owner Joseph Medill was elected mayor, vowing to outlaw the construction of wood buildings throughout the city. Members of Chicago’s working class, including German immigrants on the city’s North Side, protested against Medill’s “fireproof” proposal, saying it would make it too expensive for them to build new homes.

In the face of this opposition, aldermen compromised. Instead of banning new wooden buildings throughout the city, they expanded the part of downtown Chicago where wood structures were prohibited.

But then, after that second big fire in 1874, Chicago officials extended the restriction on wooden buildings to cover the whole city.

Elaine Lewinnek, author of the new book The Working Man’s Reward: Chicago’s Early Suburbs and the Roots of American Sprawl, says the aldermen contributed to suburban sprawl by making it cheaper to build outside the city. After they changed the law, a real estate booster reported “a brisk demand for building just outside the city limits.” (Some of those areas outside the city limits in the 1870s later became part of the city through annexations.)

Even without the big fires of 1871 and 1874, worries about fire safety may have eventually prompted aldermen to ban wood buildings. But maybe Chicago needed a disaster to persuade the City Council to take action in the face of protests from people who insisted they had a right to cheap construction.

During the rapid reconstruction after the fire, builders had trouble finding enough stone to put on their facades and terra cotta become a more common building material.

“Most of the stones popular at the time came from distant locations, and the quarries and carving facilities could hardly meet the demand,” Samuelson says. “Chicago’s small and struggling terra cotta industry suddenly blossomed from the post-fire demand, and gave birth to an industry that produced the amazing clay-clad skyscrapers of later decades, including the amazing creations of Louis Sullivan, and the gleaming Wrigley Building.”

Masengarb agrees that Chicago would have had fewer terra cotta buildings without the Great Fire. “But we certainly would have had some,” she adds. “Terra cotta production became an important industry in the Chicago suburbs — the American Terra Cotta and Ceramic Co., around Crystal Lake especially — because of the natural clay deposits here. I think this industry would have sprung up eventually, without the fire.”

Map Showing the Burnt District in Chicago, 3rd Edition; R. P. Studley Company, 1871 (Image courtesy Chicago History Museum)

What about the pattern of development — what got built where in the city and suburbs?

In their 1969 book Chicago: Growth of a Metropolis, Harold M. Mayer and Richard C. Wade wrote: “Despite the destruction, the fire did not basically alter the shape of the city.” Several experts say the fire simply sped up what was already happening.

“Things were already changing, as railroad lines and industry were crowding out housing,” Keating says. “The fire made this happen more quickly but it would have happened anyways. People moved more quickly south to Prairie Avenue or out to new suburban towns like Riverside.”

"And the shoreline downtown would have stopped at Michigan Avenue for decades, if not to this very day.”

-Lee Bey

“The fire pushed 27,000 humble homes out of the central city and the North Side, leading to fewer residences downtown,” Lewinnek says. “Yet suburbanization was already happening before the fire, in elite suburbs like Riverside and more humble suburbs too.”

In his book The Great Chicago Fire, Ross Miller writes that “the city was rebuilt along stricter class and ethnic lines” after 1871. Samors says those patterns may have turned out differently without the fire. “Many Chicagoans would have been content to remain in their old neighborhoods,” he says.

The fire also reshaped the city’s lakeshore. Debris from the 1871 fire was dumped into Lake Michigan — millions of tons of rubble, according to Miller’s book — extending the downtown shoreline farther east.

Without the fire, Bey says, “We wouldn’t have Grant Park, since the park was built on fire debris dumped into the lake. Same with the north end of Burnham Park. And the shoreline downtown would have stopped at Michigan Avenue for decades, if not to this very day.”

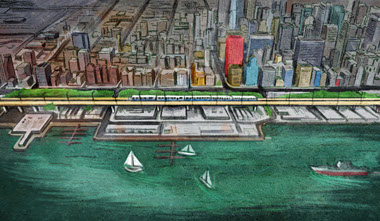

Compare: Less lakefront?

Architectural critic Lee Bey weighs-in on the contours of the city, had it been spared the conflagration. “We wouldn’t have Grant Park, since the park was built on fire debris dumped into the lake,” he says. “And the shoreline downtown would have stopped at Michigan Avenue for decades, if not to this very day.” (Image: Google Earth / Illustration: Erik Rodriguez)

“We would have had a more traditional shoreline, such as the one in Detroit,” Schwieterman says.

“The lake might just have ended at Michigan Avenue and the Illinois Central trestle in the lake would have remained, even if it was rebuilt and modernized,” Samors says.

But other experts aren’t so sure about this.

“I don’t know if it would have been that different,” Bales says. “Yeah, debris was thrown in after the 1871 fire. But remember, there was that whole lakefront expansion going on in later years, anyway, when the city put in Lake Shore Drive.”

“It might not have turned out so differently,” Leslie says. “The fill from the fire was used to fill in a stagnant part of the lake out to an existing Illinois Central trestle that was roughly where Columbus Drive is now. I suspect that might have been done at some point anyway for sanitation reasons, but maybe not for a while.”

And Keating says, “I don’t know that the shoreline would be very different — always lots of garbage!”

IV. Architectural

prowess

A rendering of the now-demolished entrance arch of the Chicago Stock Exchange, formerly located at 30 N. LaSalle St. Architects: David Adler and Louis Sullivan. (Image: Library of Congress)

What about the styles of architecture that burst out of Chicago in the late 19th century? How would they be different in a world without the Great Fire?

“One common myth is that right after the fire — poof! — we rebuilt our small brick/wood city with big steel skyscrapers,” Masengarb says. “But that wasn’t the case at all. For the most part, right after the fire we rebuilt things quickly and in methods of construction or styles that we already knew — two- to five-story load-bearing buildings.”

But architects from other places — including Louis Sullivan and John Root — flocked to Chicago.

Daniel Burnham was already in Chicago before 1871, but he emerged as an architect in the years after the fire. Sullivan arrived in 1873, just as economic depression hit, halting Chicago’s rebuilding. According to Miller’s book, this idle time gave young architects a chance to develop their thoughtful styles.

So, in an alternate universe without the 1871 fire, would the Chicago School of Architecture even exist?

"Creative dreamer architects like Sullivan and Root likely would have never had the incentive to come here."

-Tim Samuelson

“What is considered modern architecture — stripped down, bold in mass and form — had its origins in a reimagining of the fire by a new group of architects lured to the city by the unprecedented opportunities to build,” Miller writes. “They stayed on through the difficult days with little to do but paper architecture and study of what others before them had done.”

They began turning their ideas into actual buildings when the economy recovered in the 1880s. Many structures from the first wave of post-fire construction were torn down — just 10 or 15 years after they were erected — to make way for taller ones. Chicago became the birthplace of the skyscraper.

So, in an alternate universe without the 1871 fire, would the Chicago School of Architecture even exist?

“Creative dreamer architects like Sullivan and Root likely would have never had the incentive to come here,” Samuelson says.

And of course, that doesn’t mean Chicago would lack skyscrapers.

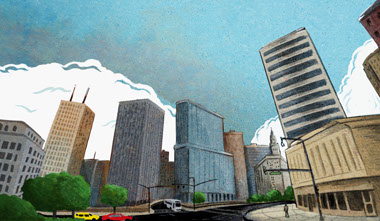

Compare : An uninspired skyline

Ross Miller, author of The Great Chicago Fire, surmises that, spared the flames, the city’s downtown would have had fewer large blocks open for development in later decades. “Chicago would likely have had its share of skyscrapers,” he says — but not as many as it does today. Picture a skyline without so many dramatic peaks. (Image: Google Earth / Illustration: Erik Rodriguez)

“The city’s existing sizable German community and other technically trained immigrant residents would have provided the technical expertise to build tall buildings if business growth demanded it,” Samuelson says. Without “dreamers” like Sullivan, Root and Burnham, “We may have gotten pioneering tall buildings anyway, but perhaps more pragmatic and utilitarian, and more superficial reflections of popular nationwide architectural styles,” Samuelson says.

Miller says the Chicago School of Architecture sprang directly out of the fire’s aftermath. “Architects were given a blank slate and generous budgets to build anything they could imagine,” he says.

But other experts say Chicago’s architectural style would have developed along similar lines with or without the fire.

“I wanna push back on that narrative a bit,” Bey says. “Chicago was very much a city on the rise before the fire, although the suddenly clean slate caused by the fire and the civic will to rise from the ashes did draw architects and developers. But even without the fire, that talent and capital would have ultimately made its way here.”

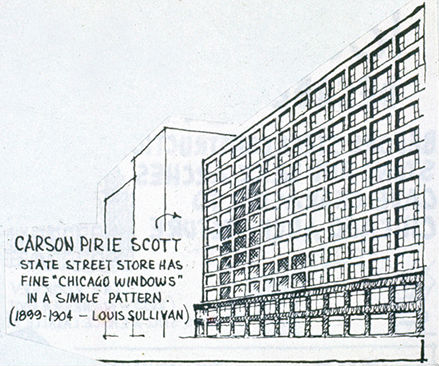

Sketch of the Carson Pirie Scott store by C. William Brubaker, 1960s.(Image: UIC Digital Collections)

Sketch of the Carson Pirie Scott store by C. William Brubaker, 1960s.(Image: UIC Digital Collections)

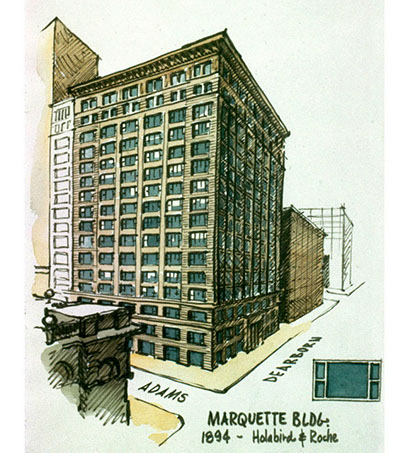

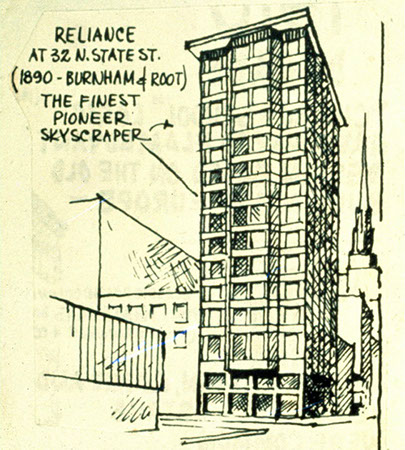

Leslie agrees, saying: “The really innovative buildings — the Reliance, the Marquette, Carson Pirie Scott — didn’t happen until the mid- to late-1890s. These buildings all happened not because of the fire, but because new materials — in particular steel and plate glass — emerged that allowed architects and builders to build much more efficient buildings. So my guess is that the Chicago School would have happened along more or less the same lines.”

“I think to some extent, young architects would still have come to Chicago,” Masengarb says, “because the city offered more possibilities for young designers than older, established cities along the East Coast. But it’s true that without the fire, that can-do, ‘I Will’ spirit of rebirth would not have been in the minds of these young architects.

Sketch of the Marquette buildings by C. William Brubaker, 1960s.(Image: UIC Digital Collections)

Sketch of the Marquette buildings by C. William Brubaker, 1960s.(Image: UIC Digital Collections)

“Big natural disasters don’t typically lead to revolutionary change in building types right away,” she adds. “The change in construction technologies and habits happens more slowly. Right after a disaster you’re thinking about more basic issues of shelter and restarting commerce — not transforming the ways that buildings are designed or built.”

Northwestern University professor Bill Savage says Chicago’s geography — “the way the lake and the river hem in the Loop area” — would have birthed the skyscraper anyway. “But without the wipe-the-slate-clean moment of the fire, I doubt very much that so much architectural and construction engineering talent would have come to Chicago en masse all at once,” he says. “At the very least, the innovation would have been slower.”

Sketch of the Reliance Building by C. William Brubaker, 1960s. (Image: UIC Digital Collections)

Sketch of the Reliance Building by C. William Brubaker, 1960s. (Image: UIC Digital Collections)

Lowe says the city’s growth would have made skyscrapers necessary anyway. “The impetus for taller buildings to hold the growing number of employees in the burgeoning American corporations would have supplied plenty of demand for the talents of Sullivan, Root and Holabird,” he says. “The requirements and challenges of these new high-rise structures would have, undoubtedly, given birth to the technically brilliant and innovative style of the Chicago School of Architecture.”

Miller says Chicago may have turned out more like St. Louis or Buffalo, N.Y. without the effects of the 1871 fire. Downtown was already changing before 1871, becoming less residential and more commercial, but the fire accelerated that transformation, Miller says.

“The fire conveniently burned out the small land owners and made it possible for developers to control entire blocks,” he says. “Without the fire, Chicago would likely have had its share of skyscrapers,” he says — but not as many as it does today. Picture a skyline without so many dramatic peaks.

V. Chicago's identity?

World's Fair, 1893, Chicago. (Image: Library of Congress)

Without the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, would another colossal event — the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 — have taken place?

“Almost certainly not,” Leslie says. “The fire was a catalyst for the city to prove itself, and the idea of the city being reborn and showing itself off to the world was part of the very earliest discussions. Chicago gained worldwide publicity because of the fire, too, and there was still sympathy and support nationwide by the time of the fair’s planning stages.”

“No,” Savage says. “The recovery from the fire was one of the selling points to give the city the fair — the idea that they could build it like they’d rebuilt the city.”

And if the World’s Fair didn’t happen, that could make some drastic differences in Chicago’s architecture and culture. The Field Museum, Art Institute and Museum of Science and Industry might not exist, at least the way we know them. The area around Hyde Park and Jackson Park would look different. Burnham’s Chicago Plan of 1909 — which was heavily influenced by his experiences overseeing the World’s Fair — might not exist. Chicago's flag was adopted in 1917. The first red star symbolizes the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. (Image: Chicago Detours)

Chicago's flag was adopted in 1917. The first red star symbolizes the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. (Image: Chicago Detours)

“The fair is the game-changer for Chicago, even more so than the fire,” Bey says. “It showcases the city to the world.”

But wait — before we fall too far down this alternate-history rabbit hole, other experts say the World’s Fair would have happened in Chicago anyway.

“I don’t think the World’s Fair depended as much on the fire as it did on the city’s growth and its boosterism,” Smith says, “though the ‘resurrection’ from the fire proved a useful hook.”

“The fair did indeed celebrate the astonishing recovery of Chicago from the fire,” Lowe says. “But let us not forget that the location of the fair was part of a national competition among the major cities of the country to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the ‘discovery’ of the New World by Columbus. Chicago, with its booming population and expanding economy and its native pride, would most certainly have been a contender for the fair.”

Without the 1893 expo, Savage says, Chicago might not have hosted its second World’s Fair, either — the Century of Progress Exposition in 1933-34. And without the Great Fire or the two world’s fairs, the Chicago flag would have only one star, he says: the one that represents Fort Dearborn.

But here’s the thing about answering “What if?” questions about history: Changing one event like the Great Fire would cause countless consequences. Chicago might still have four stars on its flag, but they would represent a completely different sequence of big events — events we haven’t even thought of.

In a world without the 1871 fire, would Chicagoans have had the same sort of spirit, attitude and drive?

When Kevin asked the question that prompted this story, he was confident that the Great Chicago Fire had an immense impact on the city’s shape today. But some of what we learned gives him pause — including the idea that a different fire might have come later anyway.

Kevin sounds almost persuaded by the historians who say the 1893 World’s Fair wouldn’t have happened. “I think we can say the city is quite different from the way it would be without the fire,” he says. “However, in what way, we’ll never really know.”

The Great Chicago Fire did more than burn down a lot of buildings. “I think rebuilding from the fire gave the city the civic will to aim higher and shoot straighter when it comes to big civic projects and city-building,” Bey says.

“What the fire did, without question, was to catalyze the city’s developers, entrepreneurs and builders,” Leslie says. “The speed with which the city was rebuilt remained an inspiration for years afterwards, and the social, business, and cultural connections that were forged internally made Chicago’s building culture a far more agile, dynamic one than other cities.”

Without the fire, “Chicago may have developed similarly,” Samuelson says, “but it may have lacked the city’s post-fire edginess.”

This might be the biggest mystery raised by Kevin’s question: In a world without the 1871 fire, would Chicagoans have had the same sort of spirit, attitude and drive? And if not, how would that have changed history? Think of a city with fewer skyscrapers, bland architecture and a lack of what Samuelson calls edginess. In this alternate universe, Chicago sounds sort of boring.

Maybe the Chicago Evening Journal was onto something in 1872. Just a year after the Great Chicago Fire, looking at the way the city was rebuilding, the newspaper said: “Was not the Great Fire a blessing in disguise?” ▪

Robert Loerzel is a freelance journalist and the author of Alchemy of Bones: Chicago’s Luetgert Murder Case of 1897. Follow him at @robertloerzel.

Sources

Richard F. Bales, an Aurora resident, is the author of The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow (2002).

Lee Bey is a former architecture critic for the Chicago Sun-Times who has blogged about architecture for WBEZ. He is now special projects manager for the University of Chicago’s Arts + Public Life Initiative.

Ann Durkin Keating co-edited of The Encyclopedia of Chicago (2004). She is the Dr. C. Frederick Toenniges professor of history at North Central College in Naperville.

Thomas Leslie, author of the 2013 book Chicago Skyscrapers: 1871-1934, is the Pickard Chilton professor of architecture at Iowa State University.

Elaine Lewinnek is author of The Working Man’s Reward: Chicago’s Early Suburbs and the Roots of American Sprawl (2014) and an associate professor of American studies at California State University in Fullerton.

David Garrard Lowe, president of the Beaux Arts Alliance in New York City, is the author of Lost Chicago, originally published in 1975 and revised in 2000 and 2010.

Jennifer Masengarb is director of interpretation and research at the Chicago Architecture Foundation.

Ross Miller, an English professor emeritus at the University of Connecticut at Storrs, is the author of The Great Chicago Fire (1990).

Carl Smith, Franklyn Bliss Snyder professor of English and American Studies at Northwestern University, is the curator and author of the Chicago History Museum’s website on “The Great Chicago Fire.” He also wrote Urban Disorder and the Shape of Belief: The Great Chicago Fire, the Haymarket Bomb, and the Model Town of Pullman (1995).

Neal Samors, who publishes books through his company Chicago’s Books Press, has written several books on the area’s history, including Downtown Chicago in Transition (2007), which he co-authored with Eric Bronsky.

Tim Samuelson is the city of Chicago’s cultural historian.

Bill Savage, a distinguished senior lecturer in English at Northwestern University, is co-editor of recent editions of Chicago by Day and Night: The Pleasure Seeker’s Guide to the Paris of America and Nelson Algren’s Chicago: City on the Make.

Joseph P. Schwieterman is director of the Chaddick Institute and a professor in DePaul University Graduate School of Public Service. He wrote The Politics of Place: A History of Zoning in Chicago (2006) with co-author Dana M. Caspall.