Displaced

When the Eisenhower Expressway Moved in,

Who Was Forced Out?

Question asked by Jillian Zarlenga

If you live in Chicago and you drive a car, you’ve probably been stuck in traffic on the Eisenhower Expressway. Oak Park resident Jillian Zarlenga sure has. “I spent a great deal of time on the Eisenhower inching towards the Harlem Avenue exit,” she says.

Sitting in traffic jams gave Jillian time to think — especially when she was working as a United Church of Christ chaplain at Elmhurst Hospital. “I had a lot of time sitting on the Eisenhower examining this huge area of land, thinking there must have been a lot of people that lived here before, and I was just curious where they all went,” she says. She also wondered about all of the buildings that were torn down. What was lost? These musings prompted her to pose this question to Curious City: “What happened to the people displaced by the Eisenhower Expressway?”

It’s a good question, and it gets even better when you add up some of the basic details surrounding the Eisenhower (or the Ike, or I-290, if you’re so inclined), which runs almost due west from Chicago’s Loop out to Oak Park and beyond.

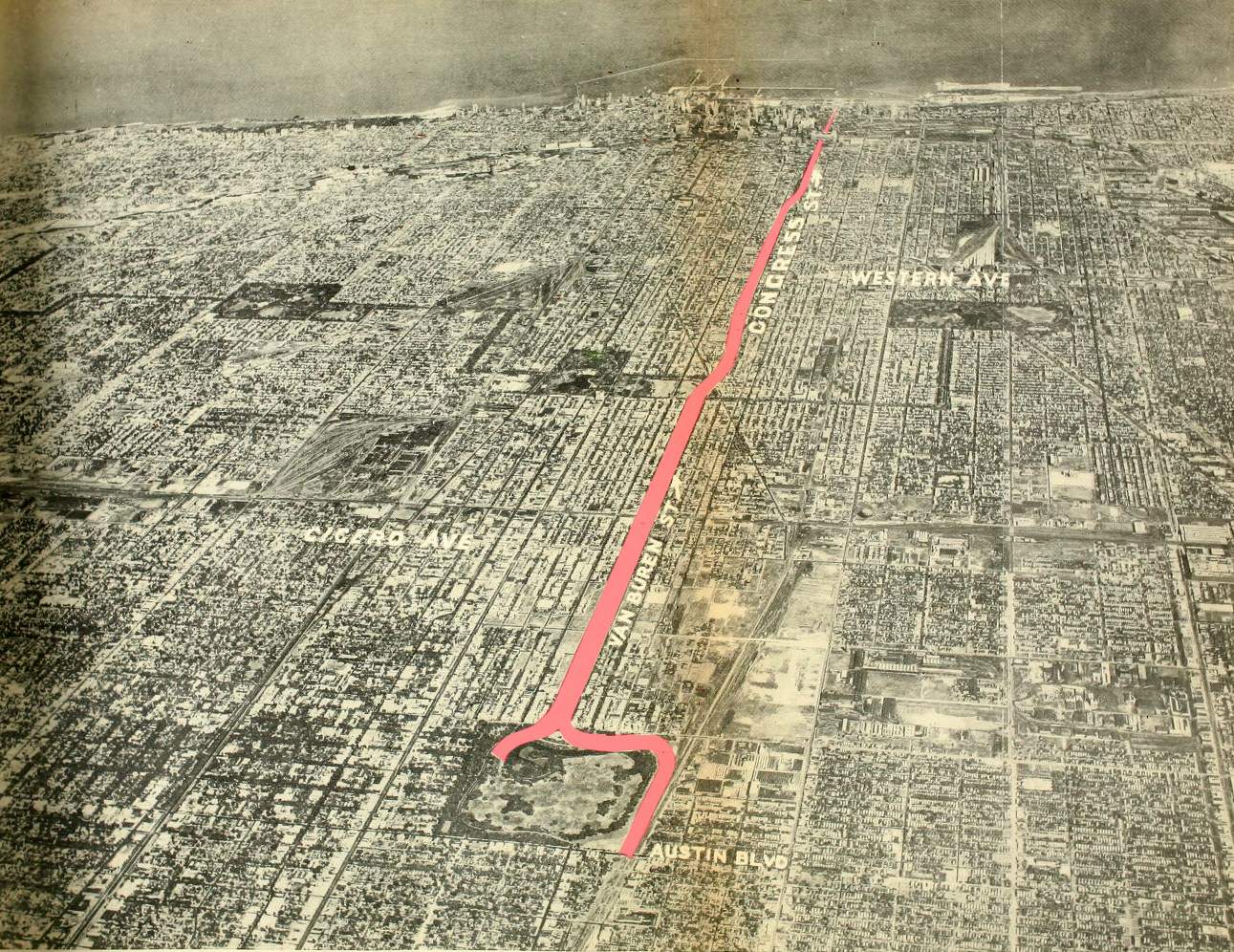

For example, the Eisenhower — built between 1949 and 1961 at a cost of $183 million — displaced an estimated 13,000 people and forced out more than 400 businesses in Chicago alone. Who were these people, indeed?

And, another reason to look at the Ike: It was the first superhighway in the heart of Chicago. However, by the 1960s — after more expressways were built, more neighborhoods were torn up, and traffic stayed as terrible as it was before — grassroots groups began fighting against these projects and even managed to kill one off.

It’s difficult to pinpoint data about precisely where the people displaced by the Eisenhower’s construction ended up. No one tracked their whereabouts. But we do have an answer for Jillian. After talking with historians and people who lived through the upheaval, a picture emerges of how the expressway reshaped the Chicago region, scattered some of the city’s ethnic communities and forever changed many lives. That picture’s best consumed in parts. We’ll move east to west along the Ike.

But first, why was the Eisenhower built at all?

A 'Grand Axis' to modernity

Built between 1949 and 1961 at a cost of $183 million, the Eisenhower Expressway displaced an estimated 13,000 people and forced out more than 400 businesses in Chicago alone. (Source: A Comprehensive Superhighway Plan for the City of Chicago, 1939)

The traffic in Chicago was so bad that people were desperate for a solution. In the 1920s and ’30s, more and more cars were filling the streets. “Cars really overwhelm the city — not just Chicago, but everywhere,” says David Spatz, a scholar in residence at the Newberry Library who’s writing a book on the history of Chicago’s expressways. “Many community groups are demanding expressways because traffic is really dangerous and unmanageable.”

The interstate highway system didn’t exist yet, but planners across the country envisioned superhighways without any stop signs or traffic lights to slow down cars. In 1940, the Chicago City Council approved plans for a local system of superhighways. Traffic was worst on the West Side, Spatz says, so that’s where the highway builders started first.

They chose to follow the path of Congress Street.

Why Congress? In a way, City Hall and its planners were following the advice of Daniel Burnham. Back in 1909, when Burnham and Edward Bennett wrote their famous Plan of Chicago, they’d proclaimed that Congress Street should become the city’s “grand axis.” Burnham and Bennett imagined Congress as a glorious boulevard from Grant Park to a towering new civic center at Halsted Street. That center was never built, but the idea of Congress Street as an axis persisted. “It was the site that had the most support … because of Burnham,” Spatz says. “It tapped into a spirit of Chicago pride.”

All of this was happening at a time when city officials were trying to get rid of dilapidated and unsightly buildings. “Expressways were seen as a way to kill two birds with one stone — to modernize the city by retrofitting it for cars and for traffic,” Spatz says. “And at the same time, clear out neighborhoods that were blighted.” Of course, it was questionable which buildings and neighborhoods qualified as “blighted.”

“It’s something that's used sometimes for nefarious purposes,” Spatz says. “It makes eminent domain easier. And certainly the people living there contested the idea.”

In the late 1940s, the Oak Leaves newspaper in Oak Park predicted that the new superhighway would replace the West Side’s “appalling slums” with “orderly dwellings where orderly people are living in health and comfort.”

The Near West Side

Beginning of the superhighway's construction. (Courtesy CERA Archives)

As the city began clearing the path for the Congress Street Expressway, the first neighborhood hit with demolition was the Near West Side. Here’s how the Chicago Tribune described the area in 1949, the year construction started:

“Today it harbors a haphazard mixture of industries and residences. … Nearly half its families have lived there more than a generation and in homes built for the most part before 1900. … Today the community population of 50,000 includes chiefly persons of Italian, Mexican, Greek, Jewish, and Negro ancestry.”

Of all the neighborhoods that the expressway sliced through, the Near West Side had the largest population of blacks in 1950. Nearly 40 percent of its people were African-American.

Jim O’Neil, who lived at 1623 W. Van Buren St. when he was a boy in the 1940s, fondly recalls a Mexican-American pal and some African-American girls who played with his sister. The Near West Side was one of those places officials called “blighted.” But O’Neil didn’t think of it that way. “I don't think our building was run-down,” he says. And after looking recently at old photos of the neighborhood, he says, “It certainly does not look run-down to me.”

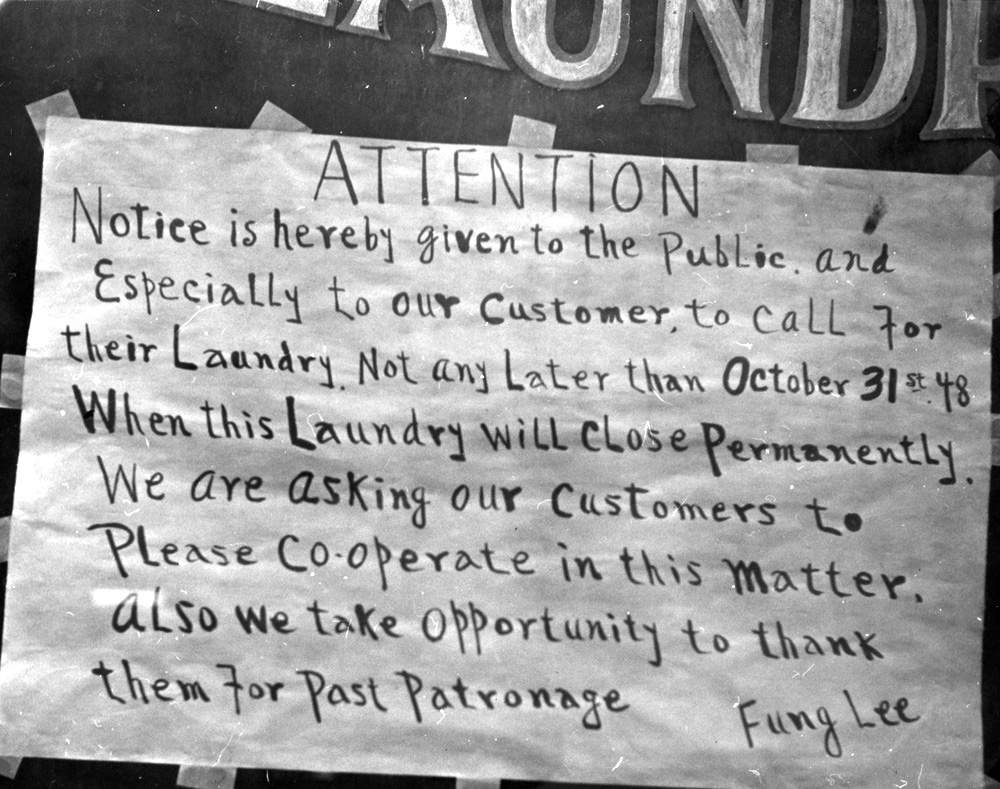

In February 1949, city housing coordinator D.E. Macklemann said some people in the neighborhood simply didn’t believe that the highway would actually get built. “One man forced us to get an eviction order from the court because he said he had been reading about superhighways for years and thought the whole thing was a dream,” Macklemann told the Tribune. “In several instances residents paid no attention until the buildings next door were being torn down.”

A laundromat's going-out-of-business sign on the Near West Side. (Courtesy University of Chicago Photographic Archive. Mildred Mead Photographs, apf2-09136

O’Neil was 8 years old when the wrecking balls arrived in 1949. “Little by little the buildings came down,” he says. “I have these vivid memories of these piles of rubble. Our building was the last one. My sister and I used to go out and play in the rubble. … There would be these piles of beams that would be burning.” He says it looked like the aftermath of a World War II bombing.

That November, the Tribune described hundreds of structures being razed on the Near West Side:

“Some of the demolished buildings were multi-story factory and commercial structures, others stores, rooming houses and wooden homes built more than 50 years ago. … The neighborhood is one of old brick and frame buildings, many sagging, with unpainted porches betraying neglect for years. Tenants in several (buildings) said they would not be unhappy to leave, but had not found new quarters at prices they could pay. ”

Chicago Mayor Martin Kennelly, who oversaw the superhighway project during his eight years leading the city, sounded proud of the destruction it was causing. “Just wiping out slums, that alone has made the work worthwhile,” he remarked in a Tribune article. “And we’ve gone far enough with the construction that any imagination can foresee the revitalization of the Near West Side, which means so much to Chicago.”

Before the Eisenhower: The Near West Side

Drag the slider left and right to view what was demolished.Near Sangamon Street and Congress Street, looking east

Near Paulina Street on Congress Street, looking west

Jim O’Neil’s family moved to Chicago’s South Side and he lost touch with everyone he’d known in the old neighborhood.

The city ran relocation offices to help people move, but that wasn’t always an easy task. The country was in the midst of a housing shortage in the years after World War II. Some people whose homes were demolished on the Near West Side “were glad to find newer and better surroundings, but the housing shortage has made it a tough job,” the Tribune reported.

Some property owners fought in court to get more money for their buildings and land. “Most settled for a negotiated price,” says Spatz, who has examined about 1,000 of these court cases. “You really can't fight eminent domain.”

Some people followed their ethnic groups to different enclaves around the city and suburbs. For example, Mexican-Americans on the Near West Side ended up in Pilsen and Little Village.

The people displaced by the expressway included residents of the Near West Side’s Greektown and Little Italy sections.

“There was a tight-knit Greek community,” says Harry Lalagos, who was born in 1944 and lived at 642 S. Blue Island Ave. “Everybody knew everybody, and everybody had cousins and relatives that all lived in the same area. … My dad had a store down there, a grocery store and a restaurant.”

“Our doors were always open,” says Harry’s younger sister, Demetra Lalagos. “People were just popping in and out. … Everybody got along.”

But then came the expressway. “I remember the construction equipment digging down and putting in the overpasses,” Harry says. “If you were standing on the Halsted Street overpass and looking west, you would see the overpasses at Morgan Street and Racine, but it was just all dirt. And every one of the underpasses would flood from the rain. … We'd build a raft and just float around in there.”

Demolition of the Near West Side for construction of the expressway, 1955. (Courtesy University of Chicago Photographic Archive. Mildred Mead Photographs, apf2-10024)

The expressway wasn’t the only project that tore up Greektown and Little Italy. A decade later, even more people — including the Lalagos family — were forced out when the University of Illinois built a campus there. “That is what really broke up the Greektown area,” Demetra says. “It was a sad time.”

Their father was forced to close his business around 1959, and the family moved near North and Harlem avenues. “It broke his heart to move out of there, because it was his life,” Harry says.

Greektown’s surviving businesses shifted north of where they had been. “As far as the residential part of it, pretty much all of the people had scattered to different parts of the city,” Harry says.

The story was similar for the Italians who lived nearby. “You can find Chicago Tribune articles calling the neighborhood a slum,” says Kathy Catrambone, co-author of Taylor Street: Chicago’s Little Italy. “I talked to many people who were here at the time, and they didn't know they were living in a slum. They liked the neighborhood. And they really felt that they were forced out.”

Catrambone says many of the neighborhood’s Italians moved to suburbs like Melrose Park, Elmwood Park and Addison. “A lot of them got on the Eisenhower and headed west,” she says. “So, you wonder if the Eisenhower wasn't there, if those people would have relocated some place in the city. But most of them went to the suburbs.”

Garfield Park

Congress Parkway and Pulaski Road, 1955. (Courtesy CERA Archive)

The expressway project continued to the west, disrupting the East Garfield Park, West Garfield Park and Austin neighborhoods. It ran through a predominantly Jewish neighborhood in West Garfield Park. “Its construction was a physical manifestation of Jewish Chicagoans’ political powerlessness,” historian Beryl Satter writes in her 2009 book Family Properties: Race, Real Estate, and the Exploitation of Black Urban America. Satter’s father was a civil-rights attorney who crusaded for black families victimized by real-estate speculators.

“It sliced the neighborhood in two and essentially destroyed it,” she writes. “Routines that had marked daily life were now impossible. The walk to the newsstand for the Sunday morning paper? Forget it; what used to be a peaceful stroll now entailed crossing eight lanes of traffic. The corner tailor? Gone. The baker? Out of business.”

"The walk to the newsstand for the Sunday morning paper? Forget it.

The corner tailor? Gone.

The baker? Out of business."

Beryl’s older brother David, who was born in 1947, recalls living in their family’s building at 3846 W. Congress St. “It was a close-knit immigrant community. … There were a lot of restaurants and shops where people knew each other,” he says. “That was the Jewish West Side. And there were Italians who lived there as well, but that was really the heart of Jewish Chicago at that time.”

Rubenstein and Glickman Deli was located on 12th Street and Independence Boulevard in Chicago's Lawndale neighborhood. The area was known as the "Jewish West Side." (Photo courtesy Spertus Institute)

Rubenstein and Glickman Deli was located on 12th Street and Independence Boulevard in Chicago's Lawndale neighborhood. The area was known as the "Jewish West Side." (Photo courtesy Spertus Institute)

The Satter family’s building was spared, but everything on the other side of Congress Street was demolished. “What was left was a huge excavation pit,” says Satter, a writer on Russian affairs who now lives in Washington, D.C. “As a child, I played in that pit. Crossed the street and went down into the excavation. I even recall — with my friend, who lived in the same building — walking all the way east, practically to downtown in the excavation and then back.”

During the project, residents complained about the long gap between demolition and construction. It created a no-man’s land in the middle of the neighborhood. Here’s how the Garfieldian, a neighborhood newspaper, described the situation in 1951:

"Organized hoodlums, vandals, morons and just ordinary scavengers loot the vacant buildings that are to be wrecked to make way for the Congress St. highway in broad daylight as well as at night time. The abundance of prowlers and other undesirable characters in the neighborhood has made residents, especially women, afraid to go out at night. Many of the buildings are used as ‘lover’s nests,’ residents reported."

“I do remember people saying that this was destroying the neighborhood — that it was tearing the heart out of the neighborhood,” Satter says. “It demoralized people to have it built there that way. ... It disfigured the neighborhood.”

The Satters moved out in 1956, heading to the South Side. Many of their neighbors moved north to other Jewish enclaves — including West Rogers Park along Devon Avenue.

The Western

Suburbs

A woman looks out the window of her Oak Park workplace at the expressway's construction. (Photo courtesy CERA Archive)

The city’s portion of the expressway was complete in 1956, but Cook County and the state continued building the road through the suburbs. Unlike Chicago neighborhoods, the village of Oak Park actually fought to change the highway plans.

Oak Parkers opposed building exit and entrance ramps from the expressway’s right lanes — where they normally go. They were against the standard clover-leaf-style ramps because those take up more land along the side of the expressway. And that would have meant tearing down more buildings. As a result of these protests, the highway builders put the ramps on the left side — in the middle of the expressway — at Austin Avenue and Harlem Boulevard. That unusual configuration is something that “a lot of people still complain about today,” says Frank Lipo, executive director of the Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest.

"It was five years of hell, to put it very bluntly."

Oak Park also stopped plans to build another interchange at either East Avenue or Ridgeland. In spite of Oak Park’s efforts to minimize destruction, about a hundred buildings were demolished in the village. Several buildings were moved to new locations. Lipo says some of the displaced people found new homes elsewhere in Oak Park.

The late Marguerite Studney said it was miserable living near the expressway construction zone in Oak Park. “It was five years of hell, to put it very bluntly,” Studney recalled. “They had a permit to work 24 hours a day. That meant, that often during the night, a pile driver was in action. And when the pile driver was pounding, the bed would vibrate. And often in the morning, you’d find that you’ve have to push your bed back three feet to the wall, where it was to begin with.”

Studney died in 2010, but Curious City Editor Shawn Allee recorded an interview with her in 2004. Fifty years after the expressway was built, she still sounded upset about it. “I think it’s been a big dividing factor in Oak Park,” she said. “It’s acted like a barrier and split the town up.”

But Lipo says, “A lot of people bought homes real close to the Eisenhower so people could get back and forth to their jobs. … It's forever changed the community, but it was going to come through anyway and so I think people have adapted to it.”

Thousands of graves had to be relocated at Forest Home Cemetery to accommodate the construction of the Eisenhower Expressway. Today, there's barely a buffer between where the cemetery ends and the highway begins. (Photo courtesy Alexis Ellers)

In nearby Forest Park, about 3,500 graves had to be moved at the Forest Home and Concordia cemeteries to make way for the expressway, delaying construction and pushing up costs. Planners talked about elevating the highway above the graveyards, but decided that would be too expensive. Many of the bodies moved at Forest Home were victims of the 1918 influenza pandemic.

On Dec. 18, 1961, the final stretch of the Congress opened, running through DuPage County and ending in Elmhurst. (In the 1970s, it was extended farther north.)

Spatz says these suburban sections of the highway project didn’t displace as many people as the parts of the Congress inside Chicago. “The city was much more densely packed at that time,” he notes. “The suburbs were much less settled at that point.”

Was the highway a factor in white flight?

(Photo courtesy CERA Archives)

So far, we’ve answered Jillian’s question about displacement by the Eisenhower in the context of the road’s construction. The 13,000 or so people who left Chicago, however, were followed by many other residents in the years that followed — enough people that the neighborhoods’ compositions were transformed quickly. Between the start of construction in the early ‘50s and the close of the decade, the Chicago neighborhoods surrounding the expressway changed from 18.8 percent to 32.2 percent black. By 1970, this area was 64 percent black.

The number of non-black residents in this area — mostly whites — plummeted from 333,716 in 1950 to 110,725 in 1970. Meanwhile, the number of black residents jumped from 77,360 to 196,482. The most drastic change happened in West Garfield Park, which flipped from 0.05 percent black in 1950 to 97.98 percent black in 1970.

Did the presence of the expressway — or the demolition that cleared the way for it — have anything to do with these population changes?

“I was not convinced that it had a role in the process of racial transformation on the West Side,” says historian Amanda Seligman, who wrote the 2005 book Block by Block: Neighborhoods and Public Policy on Chicago’s West Side.

But Christopher Reed, an African-American historian who grew up in East Garfield Park in the 1940s and ’50s, says the expressway did play a role. “The construction of the Eisenhower removed so many white families that an unnatural demographic imbalance took place,” he says. “The lure of the suburbs was powerful, especially with factories and jobs relocating into areas where the new superhighways reached. Equally, blacks sought new housing opportunities and moved into areas where vacancies occurred.”

And David Satter believes the expressway was a major factor in why so many Jewish residents and other whites abandoned the West Side, just as many African-Americans began to move in.

“It played a very important role,” he says. “The building of the Eisenhower Expressway with so little concern for the effect it would have on the community … it undercut any desire or any will to find solutions, to find ways to integrate the new arrivals. It was clear that the area was not going to stay all white. But that didn’t mean there had to be this mass white flight that took place. It didn’t mean that the whole community would have to move from the West Side to the North Side, which is pretty much what happened.

“But there were a lot of factors,” he says. “There were profiteers that were trying to spread panic and get people to move. ... But the Eisenhower Expressway, it made people feel that it was the end of an era, and the community would never be the same and it didn’t make sense to fight to stay there.”

The public's changing mindset

(Photo courtesy CERA Archives)

On Jan. 10, 1964, the Chicago City Council renamed the Congress Expressway after former President Dwight D. Eisenhower. And so, the highway’s name honors the president who’d proposed the interstate system in 1955.

Spatz says Chicagoans learned a lesson from the Eisenhower Expressway. “It took so long and it was so difficult,” he says. “You're seeing no tangible results from all of this destruction. The traffic is still terrible. A lot of people were displaced. … And so there was a good bit of bitterness about … the inability to actually carry out these projects quickly.”

As Chicago built more expressways — the Kennedy, the Dan Ryan, the Stevenson — people stopped being so complacent. They complained against demolition and displacement. Protests were one reason why another highway never got built — the Crosstown Expressway, which would have followed a north-south route near Cicero Avenue.

Here’s how Chicago Tribune reporter William Mullen summed up the Eisenhower Expressway’s impact in a 1985 article:

"The destruction of neighborhoods by the construction of the inner-city expressways sent many people to the suburbs forever. Construction of the Eisenhower Expressway, for example, destroyed long-established, flourishing, seemingly permanent Italian and Jewish communities on the West Side, robbing the city of part of its ethnic diversity. The interstates also sped the loss of business and industry from the central cities because they were either displaced by the construction or lured away by the new business opportunities offered elsewhere by the expanded highway network."

Our questioner Jillian finds that a little ironic. “The original idea was to help people get to the city,” she says. “And instead it ended up with people fleeing the city.”

Who asked the question?

The Rev. Jillian Zarlenga grew up in DuPage County and lives now in Oak Park. An ordained minister, she has worked as a United Church of Christ chaplain at Elmhurst Hospital and other hospitals, but she’s currently a stay-at-home mom, taking care of her 11-month-old daughter Rory — who joined Jillian during her recent visit to the WBEZ studios at Navy Pier, where Jillian listened in on our interview with historian David Spatz. Jillian says she was fascinated by what she heard, but sounds eager to continue looking into the question. “I want to know so much more,” she says. As it happens, her great-grandparents are buried at Forest Home Cemetery, one of the graveyards where some bodies were displaced by the construction of the Ike.