First, the artists determine what kind of cow they want to sculpt. There are seven different breeds of real-life dairy cows, which vary in size and color. Once they've made a selection, the artists study pictures, videos, and maybe even spend time on a farm.

Next, they sketch the cow's pose and any buttery scenery that will accompany it.

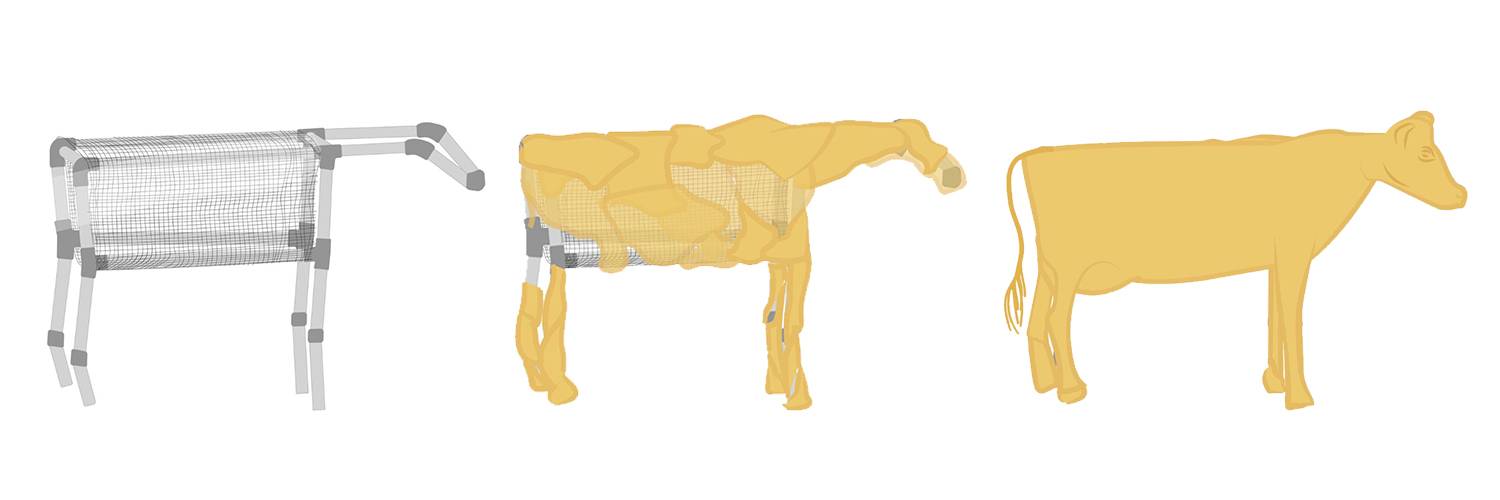

Then, it’s time to sketch out the “bones,” known as the armature, which need to be strong enough to support hundreds of pounds of butter.

The experts said they construct the armature from a variety of materials, including metal pipes, wood boards, hardware cloth, and chicken wire. Armatures can take up to four weeks to design and build, so they are usually made off-site.

Once at the fairgrounds, the skeleton is put in a display case that is cooled to around 45 degrees.

Sculptors begin by smearing layer upon layer of butter onto the skeleton. Pratt said building the base takes her about two days.

Pratt said she uses the same butter every year. Older butter has less moisture, which makes it more like clay and easier to work with, she said. The downside: It starts to smell like “parmesan cheese.”

Next, it's time to refine that mass of butter into a shape that resembles a cow. The artists use anything from their hands to cake decorating tools.

When the fair is over, the cooler is turned off and the butter softens. Pratt said she helps pack her butter back into 5 gallon buckets, careful to smoosh out any air bubbles that could cause mold. Then, it's put in a freezer, where it waits for its next incarnation.